The Farm Security Administration (FSA), a New Deal program established in 1935, was created to combat rural poverty during the Great Depression. Originally known as the Resettlement Administration (RA) before being reorganized into the FSA in 1937, its mission was to improve the living conditions of impoverished farmers and migrant workers through loans, education, and resettlement projects. While its economic efforts were critical, the FSA's lasting cultural legacy lies in its use of photography to document the struggles of rural America. These images not only shaped public perception of the Great Depression but also elevated documentary photography as an art form.

The Role of Photography in the FSA

Under Roy Stryker's leadership, the FSA launched a historical section to document the plight of America’s rural poor. Stryker understood the power of visual storytelling to sway public opinion and gain support for New Deal policies. Photographers were tasked with capturing the realities of economic hardship, creating a visual record that could humanize abstract statistics and policy reports. These photographs often accompanied articles in newspapers and magazines, serving as persuasive tools to highlight the necessity of government intervention.

The FSA's photographers were given a surprising amount of creative freedom. While they worked within the framework of Stryker’s detailed shooting scripts—which outlined specific themes and subjects—the photographers interpreted these directives through their unique artistic lenses. This blend of reportage and personal expression resulted in a body of work that remains unparalleled in its scope and emotional depth.

Notable FSA Photographers and Their Impact

Dorothea Lange’s work is synonymous with the FSA’s mission, particularly her iconic photograph Migrant Mother(1936). This image of Florence Owens Thompson, a destitute pea picker in California, has become one of the most recognized symbols of the Great Depression. Lange’s empathetic approach to her subjects resulted in images that not only documented hardship but also conveyed resilience and dignity. Her work helped galvanize public support for aid programs, illustrating the human cost of the economic downturn.

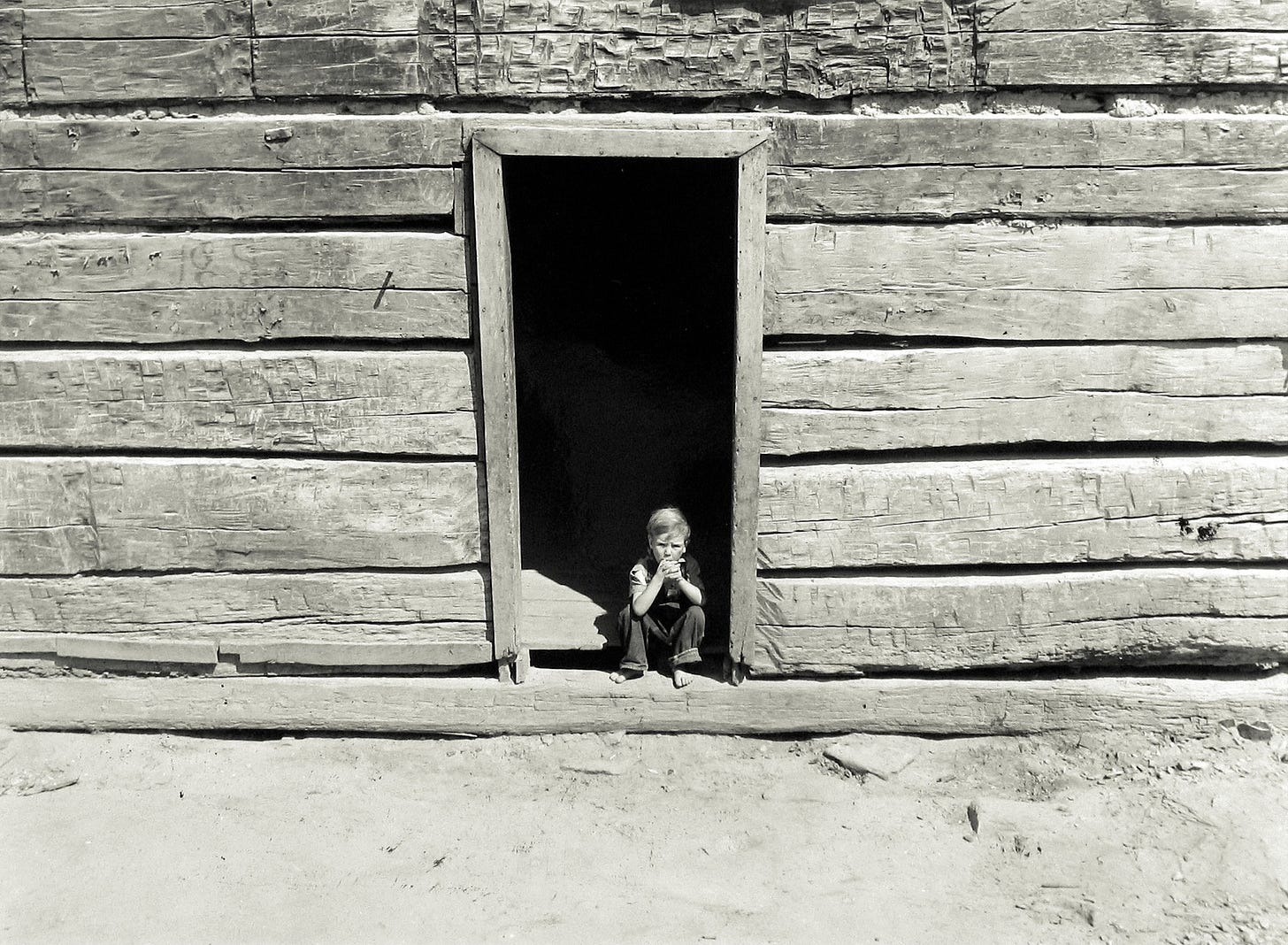

Walker Evans brought an artistic sensibility to documentary photography. His work, notably the series created in collaboration with writer James Agee for the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), focused on tenant farmers in the South. Evans’s stark, unembellished compositions captured the austere beauty of rural life, highlighting both the physical and emotional landscapes of poverty. His influence on subsequent generations of photographers cannot be overstated.

Gordon Parks joined the FSA in 1941 as its first African American photographer. Parks used his camera to document racial and economic injustices, bringing a new dimension to the agency’s work. His photograph American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942), depicting a Black cleaning woman holding a mop and broom in front of the American flag, is a powerful critique of inequality. Parks’s tenure at the FSA marked the beginning of a groundbreaking career that spanned multiple genres and mediums.

Additional Luminaries

Russell Lee: Known for his meticulous attention to detail, Lee’s work captured the nuances of daily life.

Marion Post Wolcott: Wolcott’s images of the South offer a poignant exploration of segregation and poverty, often focusing on the resilience of communities.