*All photographs are © Stephen Shames

**Book links are my Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

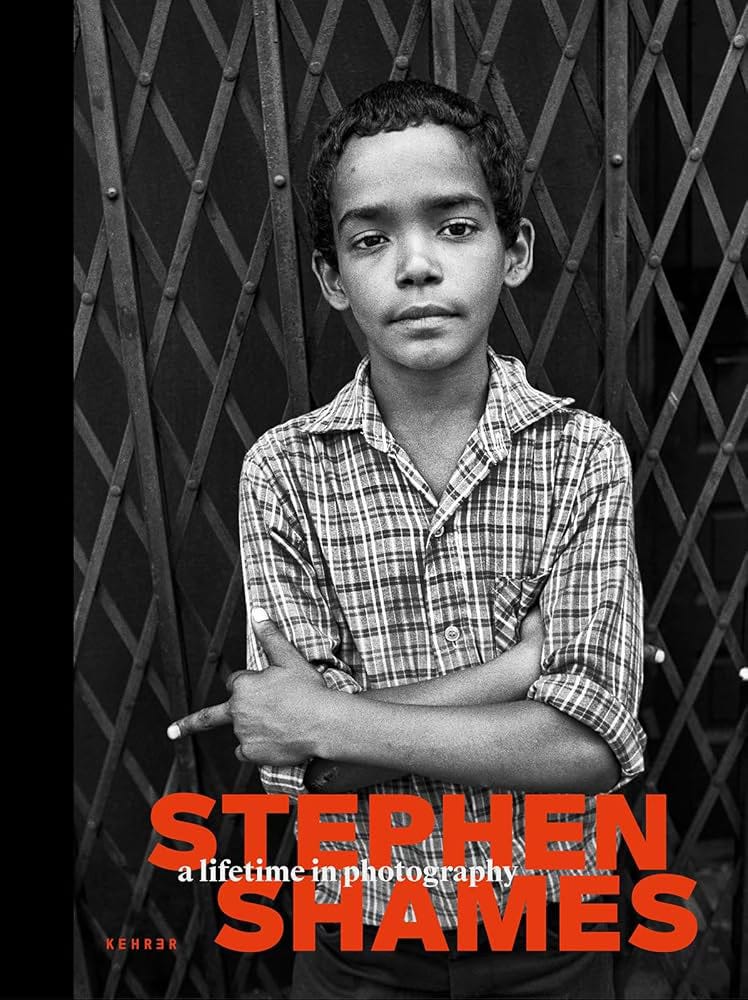

I received the book Stephen Shames: A Lifetime in Photography as a Father’s Day gift last month, and I’ll admit: before that day, I had never heard of Stephen Shames. As I cracked open the book and started flipping through the majority of black-and-white images, I was immediately struck by the power and intimacy of his photographs. It felt like discovering a whole new world of documentary photography that I’d somehow missed. I was blown away by what I saw — scenes of everyday people, captured with such honesty and compassion that I had to know more about the person behind the camera.

What made Shames’ work resonate so deeply with me is a personal connection. I’ve long been interested in issues of social class in America, especially poverty and the struggles of the working class. Those themes have always drawn my eye as a photographer. Stephen Shames has spent decades photographing exactly those issues. His images of families in poverty, kids on the streets, protesters, and prisoners – they all hit home. I found myself moved not just by the subjects, but by the empathy in his style. It’s plainspoken and real. Turning page after page, I kept thinking, this is the kind of photography that matters.

Who Is Stephen Shames?

Stephen Shames is an American photojournalist who has dedicated over fifty years to documenting social issues through his camera. He was born in 1947 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he attended the University of California, Berkeley in the 1960s. Those were turbulent times: the civil rights movement was in full swing, and anti-Vietnam War protests were erupting on campuses. As a student at Berkeley, Shames became involved in the protest movements – always with his camera in hand. In 1967, at just 20 years old, he began photographing the Black Panther Party from the inside, eventually becoming their unofficial documentarian for seven years. Imagine being barely out of your teens and serving as the eyes of history for the Black Panthers – that was Shames’ start as a photographer.

Over his career, Shames has worked on a number of major documentary projects. After his early work with the Panthers and Vietnam War protests, he turned his lens to the plight of America’s poorest families. In the 1980s, he traveled across the country, capturing images of impoverished children and families. These photos were published in the 1991 book Outside the Dream: Child Poverty in America, which won awards and brought national attention to the struggles of impoverished kids. He also spent years photographing youths in tough circumstances – from street kids in New York’s Bronx, to juveniles in the criminal justice system. In fact, Shames produced a powerful series on juvenile incarceration, shining a light on teenagers locked up in conditions few of us ever see. In 2016, he co-authored Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers, reflecting on his groundbreaking work with the Panthers decades earlier. Through all these projects, Shames’ focus has remained consistent: showing us the lives of people on the margins – the poor, the young, the overlooked.

A Camera for Social Change

Shames doesn’t approach photography as just art or journalism; for him, it’s a tool for social change. He once described photography as “a weapon of liberation,” a means of fighting for justice and social equity. In other words, the camera is his way to give a voice to those who have none. Throughout his career, he has used his images to bring visibility to issues like poverty, inequality, racial injustice, and children’s rights. He documents people who are often ignored – impoverished kids, runaway teens, incarcerated youths, activists on the front lines – and he does it with a deep sense of respect for their dignity. There’s a clear advocacy in Shames’ work: he wants these photographs to be seen so that the problems they depict can’t be swept under the rug. President Jimmy Carter once said that Stephen Shames “captured the spirit” of grassroots programs fighting to improve lives. Looking at Shames’ photos, I understand that sentiment – each image quietly insists, Look at this. This matters.

Photographs That Resonate

Looking through A Lifetime in Photography, I found myself pausing again and again at certain photographs. Each one tells a story. I’d like to share a few of those images that left the deepest impression on me, and describe what I see and feel in them:

1985, Ventura, California. In one photo, a father named Charlie sits at a small kitchen table, his eyes closed, and his young son is wrapped around his shoulders in a gentle embrace. The boy’s face is pressed against his dad’s neck, and you can almost feel the tired comfort in that hug. I learned that Charlie’s family had been homeless for two years, living in a trailer on the beach at McGrath State Park. In the soft window light of the trailer, father and son share a moment of peace amid extremely hard times. I can sense both exhaustion and love in this image – the quiet dignity of a dad doing his best, and the child finding safety in his arms. It’s a simple kitchen-table scene, yet it speaks volumes about hardship and the bond between parent and child.

May 5, 1970, Berkeley, California. Another photograph transports me to the chaos of an anti-war protest at UC Berkeley. Amid a thick cloud of tear gas, a lone protester runs forward wearing a gas mask. In his hand, he’s gripping a smoking tear gas canister that he’s about to hurl back at the police. The scene is intense – you can see other figures blurred in the background and the ground littered with debris – but the focus is on this one young man taking action. This was during a Vietnam War protest, shortly after the U.S. expanded the war into Cambodia. The image practically crackles with energy: the billowing gas, the protester’s determined stride. Looking at it, I can almost feel the sting in my own eyes and hear the shouting. What gets me is the defiance captured here – a student literally throwing the establishment’s oppression back at them. It’s an image of youth, anger, and courage all in one frame.

1985, Ventura, California (again). In another Ventura photograph, an 11-year-old boy named Kevin sleeps in the front seat of an old car. It’s early morning; the car’s windows are fogged with dew. Kevin is curled up on the vinyl seat, wrapped in a blanket, his blond head resting against the door. In the back seat, his older brother is also asleep. I know from the caption that Kevin’s family has been homeless for years, shuttling between campgrounds and parking lots. This car is essentially their bedroom. There’s something heartbreakingly peaceful about the way Kevin sleeps – children can adapt to almost anything, even a car seat – but as a father myself, it’s painful to imagine. The photo makes me pause and think about the everyday things (a bed, a home) that so many kids go without. Kevin’s small face looks content in sleep, and that contrast – a child at rest in such an unstable situation – really stays with me.

May 1, 1970, New Haven, Connecticut. This photograph is from a huge protest in New Haven during the trial of Black Panther leaders Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins. Instead of showing the crowd of 15,000, Shames zooms in on two local boys who have climbed up on a large statue outside the courthouse. One boy sits calmly in the crook of the statue’s arm, looking out over the sea of protesters. Above him, his friend – maybe 12 or 13 years old – stands on the statue’s shoulder, fist raised high and mouth open in a shout of defiance. The stone figure beneath them is impassive, almost like an unwitting prop. The juxtaposition is striking: these kids are literally rising above the crowd, turning a piece of public art into their own soapbox. One boy is composed, observing, while the other is full of passion, symbolizing the anger of the moment. To me, it’s almost a metaphor for that era – youth speaking out, climbing up where they’re not “supposed” to be, demanding to be heard. There’s a playful element (boys will climb things), but also a profound statement in that raised fist against the backdrop of the courthouse pillars. It’s an image of youthful rebellion and hope amid a very serious protest.

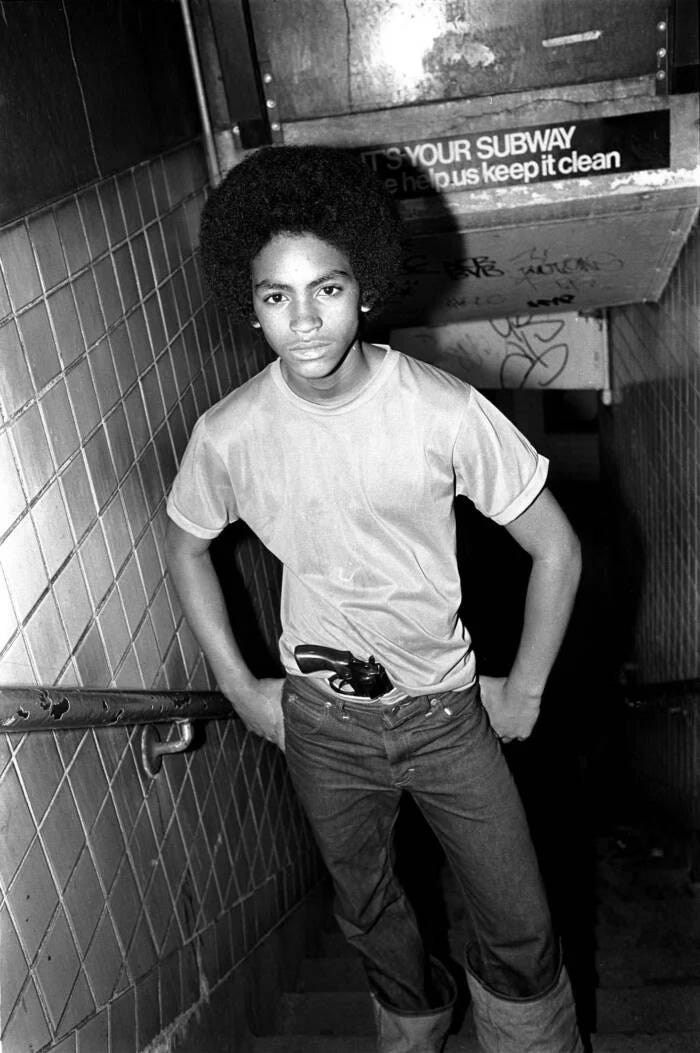

1980, New York City. In this photo, a teenage boy is emerging from a subway staircase somewhere around Times Square. He’s 15 years old, with an Afro and a steady gaze. His hands rest on his hips, showing off a handgun tucked into the waistband of his jeans. The sign above him reads It’s your subway – please help us keep it clean, an oddly ordinary message in a stark scene. The boy’s expression is what holds my eye: he looks straight at the camera, face unsmiling but not aggressive – more weary than anything. Shames notes that this teenager hustles in Times Square to survive. So here is a kid, essentially, carrying a revolver for protection or power on the streets. The image stops me cold. There’s no sensationalism to it; it’s just the reality of that moment in 1980. I find it unsettling to see someone so young in such a precarious position – forced to act far older than his years. This photograph makes me think about all the layers of story behind that gaze: how did this boy end up here? Who is he protecting himself from? It’s one of those images that reminds us that even children can be thrust into very adult situations.

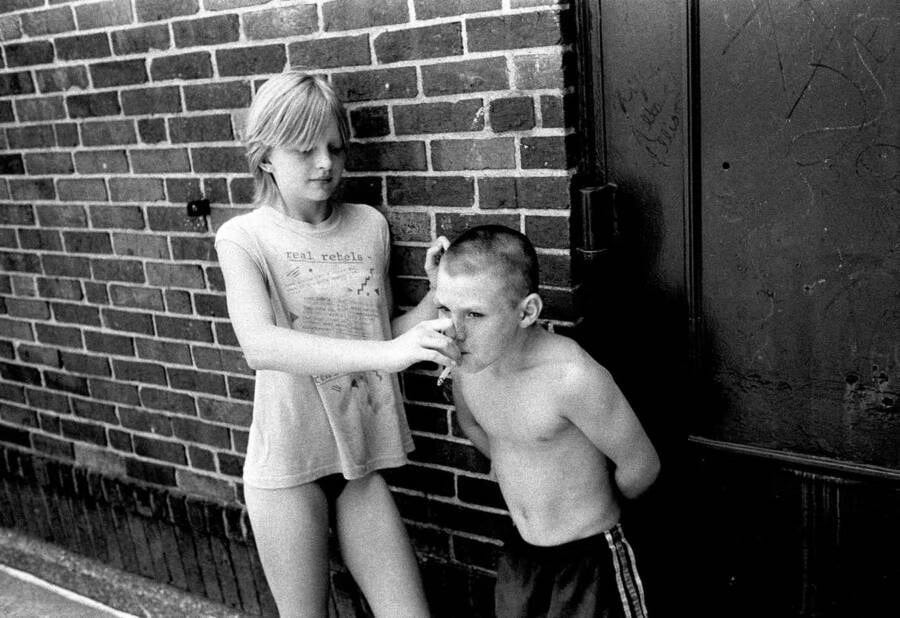

1985, Cincinnati, Ohio. Here, Shames takes us into a distressed urban neighborhood called Lower Price Hill. Against a brick wall, a teenage girl in a t-shirt and shorts is holding a cigarette to a younger boy’s lips, helping him take a puff. The boy looks no older than eight or nine, shirtless with a defiant little posture, accepting the cigarette like it’s a normal routine. This neighborhood, I’ve learned, was home to poor white families who had moved up from Appalachian states like Kentucky and West Virginia. You can almost feel the roughness of the environment in the textured brick and the graffiti-scratched metal door beside them. The girl can’t be more than 13 or 14 herself – her oversized t-shirt even reads “real rebels” – and here she is teaching a younger kid to smoke. It’s a jarring scene of childhood innocence lost. When I look at this photo, I feel a mix of sadness and concern. These kids are growing up far too fast, imitating the hard habits they’ve seen around them. There’s no adult in sight; they’re on their own. Yet, Shames doesn’t sensationalize it – he just shows it like it is. I find myself wondering what became of those kids, and how many others like them were left to fend for themselves in that community. The image carries a quiet weight: it shows a cycle that’s almost self-perpetuating, kids caught in the same struggles as the generations before them.

1984, Worland, Wyoming. This photograph is haunting in its simplicity. A teenage boy’s face appears in a small rectangular slot – the kind you’d find on a solid metal door in a jail. We only see his eye, part of his cheek, and his hand curled up near his chin as he peers out from inside a solitary confinement cell. The surrounding frame is out of focus, drawing our attention to that one sad eye. In rural Wyoming at that time, there were very few juvenile facilities, and as Shames notes, many of the teenagers locked up in places like Worland’s juvenile jail weren’t violent criminals at all. They were mostly kids who, in a larger city, might not be jailed at all. Knowing that, this image feels even heavier. The boy in the cell looks young – maybe sixteen – and not hardened or angry, just lonely and resigned. The soft light falling on his face inside that dark box of a room makes the whole thing feel very real and very cruel. I spent a long time staring at this photo. It made me think about how many youths have sat in that same position, eye to the tiny window, wondering if anyone cares. The photograph itself is quiet – no dramatic action, no crowd – but it speaks loudly about isolation and forgotten lives. It’s an image I won’t forget.

1983, Murfreesboro, Tennessee. In one of the most powerful images of the book, a 13-year-old boy named Gary sits alone in a barren county jail cell. This is an adult jail – Rutherford County Jail – and Gary is just a kid locked up with grown men. The photo shows him on a metal bunk against a plain wall. He’s hunched slightly, arms resting loosely on his lap. His face is in partial shadow, and he’s gazing down or away, with a blank, distant expression. The lighting in the cell is harsh; a broad diagonal shadow cuts across the wall, and you can see graffiti scratched into the paint behind him. There’s no one else in the frame. Juvenile detention centers existed in theory, but here was Gary, a child, sitting in an adult facility where he clearly didn’t belong. The image is heartbreakingly stark. I feel a deep sadness looking at it. Gary’s eyes look empty, like he’s already learned not to show any emotion. I can only imagine what’s going through his mind. This photograph makes me confront the reality of a system that sometimes tosses kids into the same cells as adults – out of sight, out of mind. Shames doesn’t need any caption to make the point: the picture itself is an indictment of that injustice. It left me shaken, thinking about how easily a kid’s life could be irreparably harmed in a place like that.

After spending time with Stephen Shames’ photographs, I’m deeply impressed and deeply moved. Each of these scenes – and many others in his book – carries a quiet weight and dignity. Shames shows us hard truths without sensationalism. As a photographer, I admire his commitment to telling the stories of people who are struggling, and doing so with respect and empathy. Discovering his work has been a humbling experience for me. It reaffirms something I’ve always believed: photography isn’t just about capturing pretty images; it’s about revealing life. Stephen Shames has devoted his life to revealing the lives of others, and in doing so, he helps us see the humanity in those whom society often overlooks. I’m grateful that Father’s Day gift introduced me to his work – it’s a gift not just of a book, but of insight and inspiration.

Thank you for reading. I hope you’re having a great week!

Wow! Powerful work. Great introduction. Thank you!

Powerful.